The Making of John Britten

Words by Felicity Price, author of the 2003 official biography Dare to Dream: The John Britten Story

CHRISTCHURCH CATHEDRAL WAS overflowing for John Britten’s funeral on September 9, 1995. A thousand people from all over New Zealand and some from the other side of the world filled the church and spilled into Cathedral Square, where they listened to the service on loudspeakers in the cold spring afternoon. John had died four days earlier from inoperable cancer.

The service was led by family friend and Anglican minister Louise Deans, who said: “John told me he wanted a miracle to save him from death. I forgot to tell him he was the miracle.”

Andrew Stroud, who had ridden the Britten V1000 past the chequered flag many times, read from I Corinthians, and Mayor Vicki Buck, who had presented John with a special civic award just two weeks before, concluded her heartfelt eulogy with the thought that when John arrived at the Pearly Gates, he would suggest to St Peter that he redesign them.

John’s penchant for redesigning almost anything mechanical he touched was reflected in the funeral cortège as it wound its way through the city to the cemetery. At the head of the procession was the famous pink and blue Cardinal Britten motorbike, ridden by Andrew Stroud. Immediately behind the hearse carrying John’s casket came a 1946 Triumph Gloria, a car he’d begun restoring when he was 26. Behind that, a gypsy house-truck he’d painstakingly rebuilt and furnished in his twenties, transported all the way from the Queenstown Motor Museum for the occasion. And behind that, a classic 1968 Mercedes convertible he’d also restored.

As the cortège drove round Hagley Park, within view of the 12-storey Heatherlea apartment complex John had designed and built a few years earlier, hundreds of motorbikes joined the procession. Such was John’s mana, his death was felt throughout the community. Excerpts from his funeral were broadcast that night on television news bulletins, and Holmes ran a special tribute. The nation mourned the loss of a visionary, artist, engineer, motivator, innovator and genius—but one who was also shy, unassuming and thoroughly likeable. Ten years on, people still hold a place in their heart for him, for what he achieved and what he stood for.

Like many New Zealanders who have attained international status, John overcame considerable odds, including reading and writing difficulties, under-capitalisation and constant time pressures. But these problems were also the catalyst for his innovation. He was the sort of person who never took no for an answer, who would never accept that his magnificent obsession—the Britten V1000—couldn’t be the fastest bike in its class in the world.

New Zealanders’ response to the bike’s success, especially given the fact that it was essentially produced in a small workshop in Christchurch, regarded in motorcycle-manufacturing circles as the ends of the earth, epitomises the way they feel about themselves. Even though most Kiwis know nothing about motorcycle racing, they’re proud that John and his unusual hot-pink and luminous-blue bike belong to them.

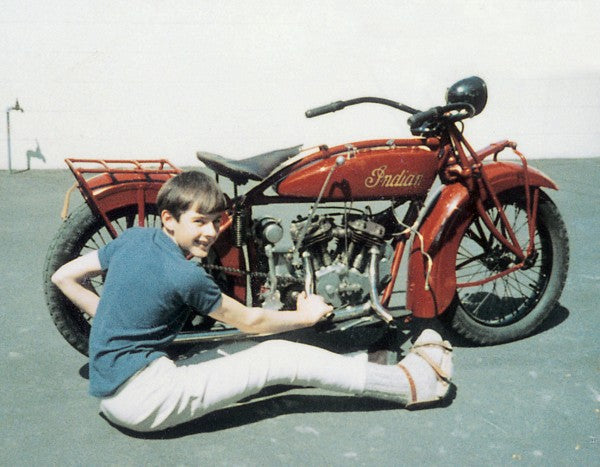

As a kid, John spent a lot of time in his father’s cycle shop and made his first go-kart at age six. By 11, he had saved enough money to make a new motorised model (top), and at 13, he began to restore an old 1927 Indian motorcycle.

As a kid, John spent a lot of time in his father’s cycle shop and made his first go-kart at age six. By 11, he had saved enough money to make a new motorised model (top), and at 13, he began to restore an old 1927 Indian motorcycle.

When Te Papa opened in 1998, the Britten V1000 was put on display, and since then it has become an iconic attraction, viewed by over a million people a year. The bike was also included in New York’s famous Guggenheim Museum’s Art of the Motorcycle exhibition. Years later, this is still touring the world, making it the most visited exhibition in museum history. Currently it’s in a Memphis museum and next year it will be in Orlando.

John and his team of hardworking volunteers made just 10 pink and blue bikes at the Britten Motorcycle Company between 1991 and 1998. All are still in existence today, three in New Zealand and the rest scattered around the world in Europe, the United States and South Africa. One, which has never been raced, resided in a glass case in its owner’s lounge in Las Vegas until last year, when it was sold. It is now displayed in a California motor museum. The others, including the original Cardinal Britten, have been raced often, though increasingly rarely in the last few years.

The world-famous Britten V1000 evolved from three precursor designs that John and his mechanically minded mates had been working on since 1985. The first two won BEARS speed trials (British, European, American Racing and Supporters) in Canterbury in 1987, 1989 and 1990, reaching speeds of 247.80 km/h.

The third was the precursor to the final design. Built from scratch with a water-cooled petrol engine, a carbon-fibre body painted green and black bearing the stylised Britten signature, it represented hundreds of hours of rushed work by John and his friends to get it ready for the March 1989 Daytona Pro Twins race. John admitted later that the Daytona trip was premature. Among other difficulties, the bike had no muffler, so one of the team went out and bought a can of baked beans, emptied it, poked a series of holes in one end and wired it over the exhaust. Luckily, the American officials took pity on the team and let the bike through—something that was to occur many times at race events in the United States. There was usually a fair amount of sympathy for the “little guys from Noo Zealand”. But no amount of sympathy could help the bike with what happened next. Roaring off the line it led as far as the first corner, then died.

Dyslexia made reading and writing a struggle, and he compensated with a strong interest in diagrams, plans, and the visual and practical aspects of design …and going fast. He as also known for enjoying a good time, and partying through the night.

Dyslexia made reading and writing a struggle, and he compensated with a strong interest in diagrams, plans, and the visual and practical aspects of design …and going fast. He as also known for enjoying a good time, and partying through the night.

On return from Daytona, it was back to the drawing board: John wanted to build not one but two bikes for his next appearance there. He believed this would double his chances of success. He was partly right: the two bikes wowed the 1990 Daytona crowd with their distinctive deep-throated thunderous growl, but problems with on-board computers that controlled fuel and ignition on both machines slowed them down, to an albeit still respectable fifth and eighth.

Rider Gary Goodfellow took these bikes home to Canada, where he worked on them for several months with New Zealand mechanic Colin Dodge. The following year, 1991, Gary won several races in Canada and Seattle and broke a lap record. He sent one back to New Zealand, where it was repainted in blue and red with the stars of the Southern Cross. The second bike was sent to Assen in the Netherlands to compete in another “Battle of the Twins” race. The bike was doing well until the electronic management system again failed, but it was undeniably fast and impressed the crowd.

In the 1991 “Battle of the Twins” at Daytona, one of the two Britten bikes retired with a broken clutch; the other was overtaken by a factory Ducati very close to the end of the race when it mysteriously slowed down.

But second wasn’t good enough for John. He had worked out that, to reach the top speeds required to win at Daytona, he’d have to radically change the bike’s aerodynamics—and he always wanted more power. “You’re never going to beat a works Ducati by building the same sort of bike,” he said at the time. “You’re going to have to do something quite radical and new.” Although his father had died recently and left him the substantial family business, he had little time to design and build new bikes and his resources were still modest compared with those of major manufacturers. The deadline for the New Zealand racing circuit was January 1992, with Daytona two months later.

John set up a workshop with second-hand lathes and milling machines in cheap rented premises in Addington. The engine was to be made there, the bodywork in John’s garage at the side of his home in Riccarton.

John had an abiding passion for speed, although during a hippie-and-yoga phase in the 1970s, on at least one occasion a donket’s ears substituted for bike handlesbars.

For years, John had been analysing the componentry of motorcycles and thinking of ways to do things better and more cheaply. He’d also spent time studying the aerodynamics of birds and how minimal wind resistance could increase the speed of a moving object. He’d experimented with motorcycle design since he was a teenager, rebuilding a 1927 Indian with a 42-degree V-twin engine before working on the three precursors, and learning from his mistakes.

Now his years of experimentation were about to pay off. With the new Britten V1000, he was starting from first principles—from the beginning. He wanted it to be lighter, more streamlined and faster than any bike before it. He could see how to improve the suspension system, the induction (the drawing of a mix of air and fuel from the carburettor to the cylinder by the piston) and the wheels.

“Any engineer would be happy to succeed in just one of these developments,” wrote Kevin Cameron in the June 1992 edition of the international Cycle World magazine. “John Britten decided to tackle them all: two new cylinder head designs, fresh aerodynamics, the forks and wheels. They all worked.”

Another motorcycle journalist, Mark Forsyth, writing in Cycle World three years later, wrote: “How to make a motorcycle: Build an engine and hang suspension and everything else from that engine. Oh, and one other thing: while you’re at it, break new ground with every component and system. John Britten did.”

Cycle World also acknowledged that the Britten had more innovation between its two wheels than most NASA space shots carried on board. “If I were head honcho at a motorcycle company in Japan, Germany, Italy or America, I’d march right down the hallway…and ask how it is that one man working in a shed in Christchurch could have out-teched my entire engineering department.” It was, the magazine cover proclaimed, “the world’s most advanced motorcycle”.

His jet boat—here broken down as John catches a fish while also summoning help—was regularly pushed to the limit and beyond.

The Britten was “built like a torpedo atop a knife blade”, the torpedo being the windscreen and front fairing and the rider’s body, the blade being the front and rear tyres and the narrow engine. To keep the bike slim, the radiator was mounted horizontally under the seat, cooled by air from ducts in the front fairing and ducted out at the back to fill the wake, increasing lift and speed. The rear shock absorber filled the space where the radiator would ordinarily be, keeping the weight forward. The slimline V-twin engine was kept at a 60-degree angle and mounted forward for better weight distribution. The distinctive blue spaghetti-like exhaust also kept the bike slim.

Apart from one or two components, the engine was made from scratch by the Britten team, the cylinder heads and ports (the apertures through which the fuel–air mixture entered, and exhaust exited, the cylinders) being the most innovative parts. Hans Weekers designed and built up the port lengths using clay models, which were then used to make casting moulds for the new heads. Front-cylinder head lugs held the rear-shock mount; rear-cylinder lugs supported the radiator and seat. Separate exhaust pipes came out of each of the four valve ports, tucking in close to the chassis to become one of the bike’s most distinctive features.

Only the crankcase, made from sand-cast aluminium alloy, was heavy. But in a fully stressed engine, strength was considered a necessity. Castings were poured in a local foundry, then brought to John’s home to be heat-treated in wife Kirsteen’s pottery kiln. Miscalculating the amount of water needed for quenching, John had quickly to fetch buckets of water from the nearby swimming pool.

All engine functions were recorded by an on-board computer, which ran an engine-management program: every few hundredths of a second, it sampled and processed temperatures, mixtures, speed, throttle position and exhaust, giving the rider a precise picture of what was going on.

The “wishbone” suspension at the front was another innovation. Traditionally, bikes had telescopic suspension, relying on sliding bushes to allow vertical wheel movement. But this newly designed system, built of carbon fibre with roller bearings inside sets of aluminium wishbone forks, could handle a lot more load while remaining free-moving, thereby absorbing bumps more effectively and giving the tyres more grip so the bike could corner faster, brake harder and accelerate more quickly without loss of control. The chassis was minimalist—“wheels hanging off an engine” (to quote one description). Almost all of it was made of carbon fibre—even the wheels (but not the tyres)—at a time before this material was widely used.

In 1994 he purchased a speedy five-litre TVR Griffith sports car which he also successfully raced a few times.

When John got a bit old for motorbike racing, he moved to construction. The Britten’s striking body grew from designs he fashioned from bent wielding rod held in place by cement from a hot glue gun.

The bike’s most eye-catching innovation was its brightly coloured bodywork. This was originally mocked-up from a frame of aluminium welding wire stuck together with hot glue to get a shape, which was then translated into a foam plug mould. The first bike had four layers of carbon-fibre cloth, with some Kevlar cloth added for extra strength where needed. This was refined in later models to just two layers.

The iridescent blue-violet paint colour was copied from a piece of hand-blown glass John had found on his overseas travels, however the hot pink took some time to grow on people. Paint specialist Bob Brookland covered both pink and blue with a clear violet pearl so they gave off the same coloured sheen.

It was the rare combination of grunt and beauty that ultimately caused the critics to rave about the Britten V1000.

That it could beat other bikes soon became evident as it blitzed its way round the world and as successive, more refined versions took to the racetrack. In 1993, Britten #2 (the one on the pedestal at Te Papa) set four world speed records for motorcycles of 1000 cc and under, reaching, in the flying mile, 302.705 km/h. The records still stand today.

The fairing eventually made from carbon fibre and Kevlar and the luridly painted machine with its intestinal-looking exhaust system has been described as a sculpture that could travel at 300 km/h.

The fairing eventually made from carbon fibre and Kevlar and the luridly painted machine with its intestinal-looking exhaust system has been described as a sculpture that could travel at 300 km/h.

Such was the unbridled power of the Britten that it became known for its rear wheelstands, often during races. The cheekily raised front wheel (on one occasion for a whole kilometre on a back straight) was an assured crowd-pleaser. But power wasn’t the Britten’s only attraction.

“It’s almost impossible to shift bikes from works of art to race bikes that work. That is John’s biggest achievement,” said Murray Aitken, an engineer with a PhD who was one of many who worked on the bike with John. “What is a work of art also works as a race bike.”

“It’s a sculpture capable of 300 km/h,” said rider Loren Poole.

“It’s the fastest work of art I’m ever going to see,” wrote Kerry Swanson in Classic Motorcycles in New Zealand. “John’s ability to combine technology and aesthetics was unique.”

“The motorbike touched people for sure, but I believe his real gift, as Sam said, was to inspire others, to show them that with minimal resources and a lot of hard work they can overcome any obstacle to realise their dream.”

In acknowledgement of John’s achievement, the Design Institute of New Zealand initiated the John Britten Award soon after his death: “to accommodate the many ways in which someone can lead the way: by example, by inspiring others, by pioneering the infrastructure, by being at the top of their field, by leading an outstanding team. John Britten developed the ‘Kiwi ingenuity’ aspect of our culture to the level of genius.”

Motorcycles weren’t the only thing John Britten designed. He became a property developer interested in architecture, but earlier, in his twenties, he staged fashion shows and designed lampstands (below) and even some furniture.

Motorcycles weren’t the only thing John Britten designed. He became a property developer interested in architecture, but earlier, in his twenties, he staged fashion shows and designed lampstands (below) and even some furniture.

Tributes to John’s ingenuity—to the “shy genius”—grew in number and volume in the 1990s and continued after his death. But it wasn’t just the bike that made him into a local hero.

Throughout his life John designed and created innumerable innovations. In his teens he crafted lightweight ski boots, a sculptured reclining leather chair and a gypsy caravan, as well as rebuilding the vintage Indian motorcycle. In his twenties, he made his girlfriend a silver watch and crafted a novel hang-glider, before becoming involved in a burgeoning business making and selling handcrafted, stained-glass leadlight lamps.

For years, he worked on the painstaking restoration of the stables behind Mona Vale, transforming them from a derelict squat into the beautiful family home they are today. They feature many design innovations, including hydraulic conservatory windows that open and close automatically when the weather changes. He even made his own bicycle-operated lathe to turn the big Oamaru stone pillars.

While building his own home in his dwindling spare time, John was also developing a new building system using foam-filled (and therefore lighter and cheaper) Oamarustone tiles. Construction was slowed from time to time by frenetic activity around the bike, but the house was eventually completed and remains a low-maintenance, energy-efficient, attractive family home, with stunning views over Christchurch.

John’s final project, and one that was said to have contributed to his untimely death, was the visionary and massive Cathedral Junction complex behind Cathedral Square. After the bikes were successful, it was his next big project. He acquired a city block of land and envisioned a vast glass-roofed structure along the lines of old European railway stations with several levels of shops and a soaring central atrium. When he learned of the plan to resurrect trams in Christchurch, he managed to get them diverted through the complex, but when he died, construction work stopped. The complex was eventually completed by another developer to very different plans.

Although the final design is something of a compromise on what he originally intended, it remains a tribute to his vision for an architecturally creative transport hub surrounded by hotels, apartments, cafés and restaurants.

John was passionate about everything he did, throwing himself into each project with total absorption and dedication, working long hours—often all night—and pushing himself and others to the limit to reach impossible deadlines. The thirst for speed that drove him to create the fastest motorcycle in the world in its class also attracted him to fast cars (his ultimate possession was a TVR Griffith) and a jet boat that he pushed up rapids and rivers further than most would dare. Similarly, when he skied (and he was a superb skier) he had to be faster than anyone nearby.

Needless to say, his need for speed resulted in more than a few spills, injuries and, in the case of the jet boat, sinkings. But his supreme confidence and seeming lack of fear encouraged all those around him to feel reassured that everything would be fine.

There were only a few occasions when it looked as though he might start to slow down, the first when he came off one of the precursor bikes and ground down the side of his foot and ankle and was in much pain, unable to walk for some time. Subsequent injuries—such as when his hang-glider crash-landed from 10 m up (hurting his tailbone and cracking his pelvis), or when he fell from the upper floor of the old stables he was transforming into his home—never seemed to faze him. It was while he was paying one of his visits to the hospital’s emergency department that he met Kirsteen for the first time.

With his good looks and engaging shyness, John had attracted a succession of beautiful girls over the years. But this time he had met his match. Because Kirsteen was modelling for top magazines in the fashion capitals of the world, the lengthy courtship that ensued was an international affair. The two were married on Queen’s Birthday 1983 at the Mona Vale home John had persuaded his friends to help finish in time. The occasion was the first of many successful parties at the stunningly designed house.

The honeymoon incorporated one of Kirsteen’s modelling assignments, in Fiji, and after the birth of son Sam (1983) the assignments continued in Europe, with Sam in tow. Two more children followed—Isabelle and Jessica—and despite long hours working on the bike and his property developments, John did his best to make special time for his offspring.

With Sam, he constructed a go-kart (reminiscent of one he’d made for himself as a child), undertook numerous back-country expeditions, and went skiing and snowboarding. Sam, fearless like his father, became an expert trick snowboarder.

Isabelle remembers always wanting to do what her father was doing, missing him when he was away a lot, and treasuring the times they shared making things such as picture frames.

Jessica recalls her father always sketching. “There’d be paper for miles,” she says. “We’d be sitting down at dinner and he’d pull out a napkin and start drawing something. He never stopped thinking of things.”

After his death, the Design Institute of NZ established a John Britten Award for excellence in any area of design. At the same time as the bikes were under development, John and his wife Kirsteen were busy raising three children—Sam, Isabella, and Jessica.

Sometimes, the children and Kirsteen would accompany John to bike races, especially in New Zealand, cheering their father’s creation from the sidelines. But all three children remember him frequently being away, and how tired he would get.

When the family went on holiday, Kirsteen said, John would typically spend the first couple of days sleeping, completely blobbed out. But then he would start getting out bits of paper and doodling again, and she knew he was coming right. There were many happy family times, as the full family photo albums attest.

There is no doubt that John’s name and achievements still inspire people. “OK—so he made a fast motorcycle. But I still think inspiration was his greatest gift,” says Sam.

Many called John Britten a genius. If genius is a mixture of creativity, practicality, tenacity, untiring hard work, leadership, the knack of motivating a team and the ability to overcome obstacles, then he was indeed a genius.

There is no doubt he was a visionary, forever thinking of new and better ways that were more innovative and stylish than anyone had come up with before. “He had an incredibly creative mind. He could see the possibilities and the beauty in things the rest of us could not see,” says Vicki Buck, ex‑mayor of Christchurch.

Britten motorcycles did well in a number of races throughout the world—including here at Tsukaba in 1998 several years after John’s death.

The Sir Richard Hadlee Award for “outstanding contribution to Canterbury sport and achievement” in 1994 was just one of many accolades John Britten received. His wife Kirsteen is a former Miss Canterbury and was a top international model.

But he could also make his dreams a reality. He had the tenacity, some would say the pig-headedness, to persist with something, even if it took him endless days and nights, month after month of hard labour, to make it fast enough or beautiful enough to meet his demanding standards. And there was so much he wanted to do: he crammed into his 45 years more than most people fit into twice that.

“John would work around the clock for days on end, taking catnaps on a squashed-out carton on the concrete floor by the bike when he got too tired to function,” says long‑time friend Kit Ebbett.

A perpetual lack of resources was another factor that made John’s achievement with the bike so special. Unable to read or write very well because of dyslexia, he compensated by intricate, detailed drawings. And what he lacked in cash he made up for by buying the tools he needed second-hand or by making them himself, by devising cheaper methods, and by persuading his friends and a wide circle of craftsmen—artisans, artists, engineers, machinists, mechanics, fibreglass experts—to help him get the job done. His leadership abilities enabled him to mould those he drew into a team and motivate them all to work long hours for little or no financial reward. Yet for many, it was the most exciting project of their lives.

“The greatest gift John had was to teach people how to come together with different skills and realise a dream.People who would never normally have done what they did came and helped him because they believed in the dream,” says his sister, Dorenda.

“He was an inspiring guy to work with, the way his mind worked,” says auto engineer Allan Wylie. “You couldn’t help but be drawn in because he was doing such big things—the sort of things none of us would do ourselves.”

“It was the hardest I’ve ever worked in my life, but John made you want to succeed with him and you felt those bikes were a part of you. I would do it again tomorrow if I could,” says fellow mechanic Tim Stewart.

John had plenty of schemes and dreams, right until the end. Even on his deathbed he was working on drawings for an Indian Motorcycle Company series of Britten bikes. Unfortunately, Indian went into liquidation and the plans came to nothing. Without John’s motivating force, his ideas never came to fruition. After the last of the 10 promised Britten hand-made bikes had been completed, the Britten Motorcycle Company faded to a shadow of its former self, although it still sells Britten merchandise.

John Britten died from cancer on September 5, 1995, and thousands viewed his funeral procession from Christchurch Cathedral. A Britten V 1000 motorbike led the hearse, which followed by a succession of John’s favourite vehicles. These included a Triumph Gloria, Mercedes sports car and “gypsy caravan”, a vehicle he had meticulously restored many years before as a mobile observatory for studying bird flight—another of his enthusiasms. A 35 ha reserve on the Port Hills has been named after him, and the Britten has been placed sixth on a list of the world’s 100 top bikes.

John Britten died from cancer on September 5, 1995, and thousands viewed his funeral procession from Christchurch Cathedral. A Britten V 1000 motorbike led the hearse, which followed by a succession of John’s favourite vehicles. These included a Triumph Gloria, Mercedes sports car and “gypsy caravan”, a vehicle he had meticulously restored many years before as a mobile observatory for studying bird flight—another of his enthusiasms. A 35 ha reserve on the Port Hills has been named after him, and the Britten has been placed sixth on a list of the world’s 100 top bikes.

He had plans for a single-cylinder bike that weighed less than 100 kg, for a motorised scooter, carbon-fibre bicycles, man-powered flight, a flying car, lightweight commuter cars with engines in their wheels, and for the architecturally stylish Cathedral Junction. The single-cylinder engine got to 75 hp at first try and there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that it would have reached the desired 90 hp if John had still been around. But without him to drive the projects along,they came to a halt.

“You don’t realise someone’s potential until they’ve gone,” says long-time Britten machinist Rob Selby. “It was evident we needed someone to hold us together. But without him, we couldn’t get everyone to agree and we all went our separate ways.”

“If John had been lucky enough to just have a health scare and not a death sentence, I believe he would have gone on inventing and designing until he dropped,” said Kirsteen. “He was never going to run out of ideas.”

“The motorbike touched people for sure, but I believe his real gift, as Sam said, was to inspire others, to show them that with minimal resources and a lot of hard work they can overcome any obstacle to realise their dream.”

As a kid, John spent a lot of time in his father’s cycle shop and made his first go-kart at age six. By 11, he had saved enough money to make a new motorised model (top), and at 13, he began to restore an old 1927 Indian motorcycle.

As a kid, John spent a lot of time in his father’s cycle shop and made his first go-kart at age six. By 11, he had saved enough money to make a new motorised model (top), and at 13, he began to restore an old 1927 Indian motorcycle.

Dyslexia made reading and writing a struggle, and he compensated with a strong interest in diagrams, plans, and the visual and practical aspects of design …and going fast. He as also known for enjoying a good time, and partying through the night.

Dyslexia made reading and writing a struggle, and he compensated with a strong interest in diagrams, plans, and the visual and practical aspects of design …and going fast. He as also known for enjoying a good time, and partying through the night.

The fairing eventually made from carbon fibre and Kevlar and the luridly painted machine with its intestinal-looking exhaust system has been described as a sculpture that could travel at 300 km/h.

The fairing eventually made from carbon fibre and Kevlar and the luridly painted machine with its intestinal-looking exhaust system has been described as a sculpture that could travel at 300 km/h. Motorcycles weren’t the only thing John Britten designed. He became a property developer interested in architecture, but earlier, in his twenties, he staged fashion shows and designed lampstands (below) and even some furniture.

Motorcycles weren’t the only thing John Britten designed. He became a property developer interested in architecture, but earlier, in his twenties, he staged fashion shows and designed lampstands (below) and even some furniture.

John Britten died from cancer on September 5, 1995, and thousands viewed his funeral procession from Christchurch Cathedral. A Britten V 1000 motorbike led the hearse, which followed by a succession of John’s favourite vehicles. These included a Triumph Gloria, Mercedes sports car and “gypsy caravan”, a vehicle he had meticulously restored many years before as a mobile observatory for studying bird flight—another of his enthusiasms. A 35 ha reserve on the Port Hills has been named after him, and the Britten has been placed sixth on a list of the world’s 100 top bikes.

John Britten died from cancer on September 5, 1995, and thousands viewed his funeral procession from Christchurch Cathedral. A Britten V 1000 motorbike led the hearse, which followed by a succession of John’s favourite vehicles. These included a Triumph Gloria, Mercedes sports car and “gypsy caravan”, a vehicle he had meticulously restored many years before as a mobile observatory for studying bird flight—another of his enthusiasms. A 35 ha reserve on the Port Hills has been named after him, and the Britten has been placed sixth on a list of the world’s 100 top bikes.